Lessons from a conversation with Dr. Andrej Holm, assistant professor at the Department of Urban Sociology at Humboldt University, Berlin

My key takeaways from Berlin:

- Capitalist housing markets alone cannot meet housing needs for all income levels.

- Activism is critical for encouraging policies that address affordable housing concerns.

- Policymakers should make choices about housing with a long-term lens.

- Well-established and enduring subsidy programs are critical for scaling up affordable housing.

What makes Berlin’s story about affordable housing unique?

In 1945, Germany and Berlin were divided into East and West, with the West controlled by the capitalist Allied Powers and the East under the Soviet Union’s communist rule. Germany was reunified as one country in 1989. History is written by the winners, and East Germany (the German Democratic Republic, or “GDR”) is typically demonized as a police state. However, the GDR offered vast social programs, including state-financed and state-managed housing that had legally defined rent limits. The right to housing was even guaranteed by the GDR constitution. The average rent burden in the GDR was approximately only 5% of tenants’ income. (As a dramatic point of comparison, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development defines up to 30% of income to be an appropriate rent burden, though 12 million U.S. households pay more than 50% of their income for rent.) The unfortunate downside to the GDR’s sweeping socialist housing policy was that historical housing stock (housing built before the GDR was established in 1949) was consistently neglected and there were low standards for housing preservation.

After German reunification in 1989, most state-managed housing was privatized. Privatization was one of the main goals of reunification, and economic policies required or encouraged this privatization. Historical housing stock that had come under GDR ownership was returned to the prior owner or their heirs. GDR-era housing companies were required to sell 15% of their housing stock built under the GDR.

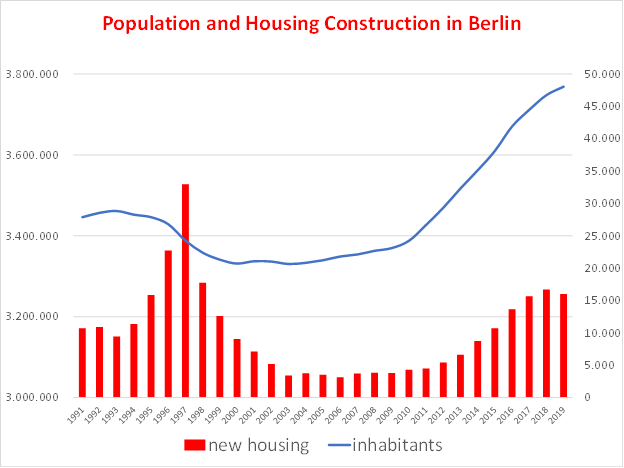

In the transition from a socialist to capitalist economy, housing inevitably became a market issue. Governments in Berlin and Germany provided large tax reductions to private investors to kickstart the housing market in the East. The idea that “the market” would create stable housing became widely accepted as blame and disdain for the GDR’s social policies grew. The illusion that the market could guarantee affordable housing for all was veiled by the combination of population loss in 1990s and the construction boom resulting from tax incentives. As a result of these opposing trends (population loss + construction boom), Berlin became one of the cheapest capitals in Europe.

Various issues led Berlin to the brink of bankruptcy 10 years after reunification and, under the conditions of urban austerity, Berlin’s government initiated a second wave of housing privatization. More than 220,000 of the remaining public housing units were sold to private owners during this time, representing nearly half of the rental housing stock. To put the nail in the coffin, all social housing subsidy and rent regulation programs were ended in 2001.

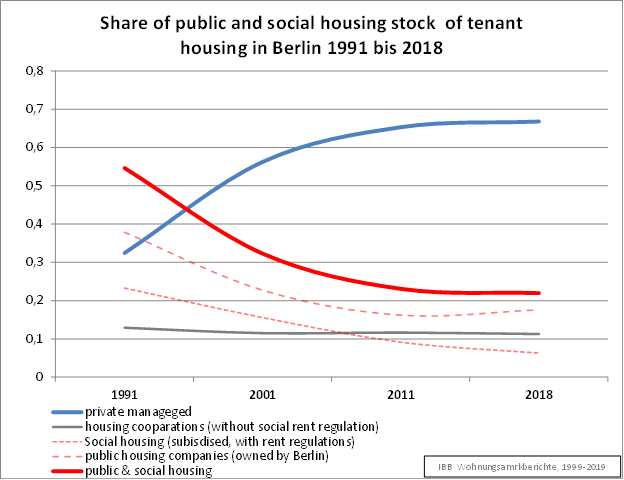

The accumulation of these changes led to dramatic shifts in Berlin’s housing market. In the early 1990s, private landlords controlled only 33% of the rental market, while 55% of all rental housing was either publicly owned or subsidized and rent-regulated social housing. By 2018, after the market was privatized and social housing programs were cut, the private sector dominated more than 67% of the rental market. Only 22% of rental units remain socialized or publicly owned.

Berlin’s post-reunification shift toward neoliberal policies and an unanticipated population growth transformed Berlin’s relatively relaxed majority-socialized housing market into a city that today has a housing affordability crisis.

What is the state of affordable housing in Berlin today?

Berlin is experiencing a housing crisis that can be measured in two distinct ways: (1) as a housing shortage and (2) as an affordability crisis. The population has increased dramatically since the 1990s, when vacancies were high and widespread housing affordability challenges seemed unimaginable. (1) High population growth in the last decade has outpaced low rates of new construction. Approximately 200,000 units must be constructed by 2030 to house Berlin’s population. (2) Income levels and rent prices are incongruent, and Berlin needs 300,000 more affordably-priced apartments for its low-income citizens.

Berlin’s market rate housing industry, which developed after reunification in the 1990s with the support of tax incentives, is not meeting market demands. For example, there are not a sufficient number of units for middle-income renters, causing ripple effects that are most problematic for the lowest-income earners who cannot access the limited social housing. These middle-income renters stay in their $650/month social housing units because the next available rents the market offers are too high for their middle-income salaries. As a result of this gap in the market, they cannot vacate their affordable apartments to make them available for lower-income tenants.

To achieve housing affordability in Berlin, affordable housing construction must increase, tenant protections must be instituted, and rent prices must be lowered. Private investors and owners have reacted to recent tenant protections and rent regulation by announcing that they’ll stop maintaining and modernizing their existing units and will not invest in new construction. To counteract this market reaction, after two decades of intentional privatization and social housing cuts, Berlin is beginning to increase its public housing production. At this point, public housing companies unfortunately do not have the capacity to develop the 200,000 new affordable housing units needed. Further, Berlin’s current social housing programs that provide rental subsidies and loans for affordable housing development shift and change every few years, making it impossible for the social housing industry to stabilize or thrive. There is not an established national program that incentivizes social housing production akin to Low Income Housing Tax Credits in the United States, which is credited with stabilizing and incentivizing affordable housing production.

Addressing housing affordability through another policy lens, the state of Berlin implemented a new rent cap law in February 2020, freezing all rent prices for the next 5 years and requiring that extremely high rent prices decrease to average levels. This new law, called Mietendeckel, is welcomed by a majority of tenants but strongly disputed by private landlords. Policymakers have recognized the necessity of responding to the housing crisis, though there is a long way to go.

If you could wave a magic wand and change any one policy at any level of government, what would it be and why?

Never sell public land! And, relatedly, make it possible for the land that once owned by East Berlin to be returned to the government for social housing. The social housing that was privatized after reunification should have been preserved as social housing under government ownership, and Berlin is now suffering the consequences of selling its housing stock as the population increased beyond what was anticipated. If decisions were made with a 10-15 year lens rather than focusing on immediate needs, East Berlin’s social housing would not likely have been sold. Counter to the expectations of WWII’s victors, capitalist markets are not meeting Berliners’ needs.

What makes you hopeful about housing in Berlin?

In response to the housing crisis, tenants’ rights groups and housing advocates have become more organized and successful in the past decade. They increased their organizing efforts in the 2010s, specified their demands, and had great successes in the 2016 elections. This has already led to positive legislative changes, such as requiring that social housing organizations have a mission to serve low-income households and the passage of the Mietendeckel rent caps. Recently, grassroots organizers started a movement calling for the city to expropriate large private landlords and transfer their housing stock to public ownership. Petitions calling for this referendum were successful, and the government is now considering the legality of this idea.

What are effective ways to include the people most impacted by affordable housing issues in government-level decision making?

It’s crucial that tenants’ voices are at the center of grassroots housing initiatives, and that elected officials partner with grassroots groups to develop effective housing policy. Tenants’ groups in Berlin evolved from protesting about general frustrations with landlords and rent increases to creating specific policy platforms. Their sophistication has garnered results: Berlin’s new government coalition in 2016 included these grassroots tenant groups in conversations at early stages of their policymaking. As a result, recent housing policies (such as Mietendeckel) have been responsive to experiences of those who have been displaced and cannot afford market rents. Ideally, as grassroots groups continue to empower low-income tenants to specify their demands, politicians will respond to their pressure by seeking their collaboration.