Lessons from a conversation with Eva Bauer, Head of Housing Economics, Austrian Federation of Limited Profit Housing Associations

My key takeaways from Vienna:

- The prevalence of social housing in Austria is uniquely tied to its history, and its successful model would be difficult to replicate in most countries today without major political shifts.

- National policies should hold affordable housing owners to strict financial responsibility standards and regulate affordable rents for many levels.

- Economic policies can be structured to enable citizens to accumulate sizeable savings, which can in turn contribute to maintaining social housing without as much subsidy.

- Even with a robust social housing system, it can still be challenging for disadvantaged groups like immigrants and refugees to secure affordable housing.

What makes Vienna’s story about affordable housing unique?

For over a century in Vienna and throughout Austria, affordable housing has been widely available for much of their low- and middle-income populations. In the early 1900s, the population in Austria was increasing while its already-horrible housing conditions were worsening. Taking matters into their own hands, twenty cooperatives were founded in 1910 with the mission to develop new housing. The co-ops were well-organized but needed funds to build new housing at the necessary scale for its members. In response, the Austrian government established its first loan program providing subsidies develop housing. In exchange for the subsidy, the co-ops agreed to maintain housing affordability and limit their profits. These founding co-ops required a commitment of 2,000 hours of labor per family member to be eligible for lotteries of the newly developed units.

While the co-op housing model of the 1910s was likely driven by a small middle class, they set a precedent for government-subsided housing that grew to serve a broader majority of the population. Following their lead and recognizing the need for affordable housing, Vienna’s government established its own public housing program in the 1920s. Its development outpaced the co-ops’ through the start of WWI in 1939.

The successes of citizen-led housing co-ops and government-led public housing from the beginning of the 20th century wove the fabric for affordable housing regulation and industry throughout Austria. Federal Limited-Profit Housing regulation outlines rules for later-established “limited-profit housing association” models (akin to non-profit housing ownership in the US), cementing the crucial role limited-profit housing plays in Austria today. (While municipalities continue to manage their own public housing, government-owned housing hasn’t been developed for 20 years because limited-profit owners build and manage housing so efficiently.)

As further proof that Austria’s policies have consistently prioritized housing affordability, it’s worth noting that the Austrian Constitution even addresses social housing affairs (i.e. provision of affordable housing) in its Volkswohnungswesen clauses, and the Wohnbauförderungsbeitrag tax requires that 1% of an employee’s gross income is contributed toward housing subsidies. The legacy of early 1900s housing co-ops in Austria have had profound effects, leading to today’s robust limited-profit housing market that provides permanently affordable housing to many income levels.

What is the state of affordable housing in Vienna today?

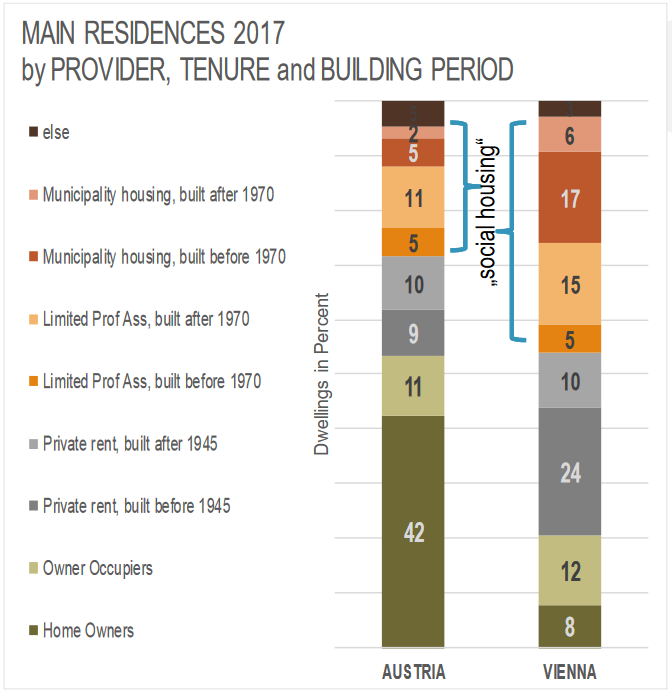

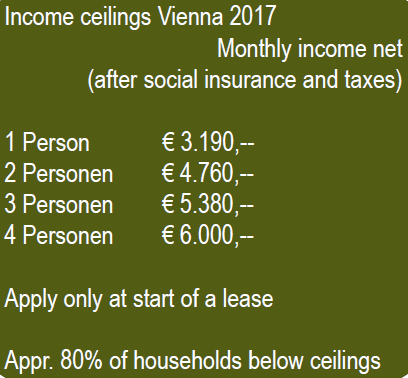

Approximately 43% of housing in Vienna is considered affordable “social housing,” the second highest rate in Europe. Tenants pay an average of only 20% of their income toward rent due to effective social housing and rent control measures in place to ensure affordability. 43% of Austrians are renters (the third highest rate in Europe) and 60-80% of the population is eligible for social housing.

In exchange for low rents, many limited-profit housing residents pay a down payment of $20,000-$40,000 per unit, which is calculated to mirror the 2,000 hours of labor that co-op members were required to contribute in the early days of Austria’s social housing. Public funds provide low-interest loans to lower-income groups for these down payments. The down payments contribute to building operations and debt service payments, and are returned to residents when they move out. There is evidence that a positive side effect of incentivizing citizens to save toward down payments for rentals rather than home ownership shielded Austria from experiencing a severe financial crisis in 2008; the subprime mortgage crisis had less of an impact in Austria, where there are far fewer home mortgages (and, conversely, more rentals) relative to other countries.

Economic Sidebar: I was stunned to learn about the $20,00-$40,000 down payment required for some limited-profit housing renters. In Austria, both affordable housing and wealth accumulation are more accessible than in the United States. I cannot fathom non-profit affordable housing owners in the US expecting such a down payment from their tenants, even with low-interest loans available. The median savings for American renters who could comfortably afford rent in 2015 was only $1,000. In Austria, economic policies allow for greater savings (e.g. power of trade unions, progressive systems of taxation, government-assisted health insurance). And, circularly, Austrian regulations that maintain low rents inevitably allow for residents accumulate greater savings. As a caveat, young Viennese and immigrants who have not had as much time to save are less likely to be able to afford the down payment expected for limited-profit housing requiring it. Even so, the fact that so many more Austrians can save substantial sums of money than their American counterparts is indicative of diverging economic policy decisions and philosophies.

While social housing is widely available throughout Austria compared to other countries, today’s housing associations today are challenged by limited land and subsidy resources. One specific challenge is that units in new buildings are not very affordable for lower-income residents due to an upward trend in land values and construction costs. These market shifts are creating a wider spread in rents between new and old buildings, which has led to concerns that ghettos will result in areas with older (more affordable) social housing stock; lower-income residents can afford units in older buildings, where rents and down payments are cheaper. The government has attempted to address this issue by creating an initiative to build smaller, more affordable units in new market-rate buildings.

If you could wave a magic wand and change any one policy at any level of government, what would it be and why?

In many countries, developers and building owners are accustomed to more profitability and freedom than Austria’s structure allows, so it likely would take a magic wand for policy makers to put affordability measures in place that could rival Austria’s. The prevalence of affordable housing in Austria is unique to its history and replicating its model elsewhere would be challenging. Most other national governments would need to start from scratch to create limited-profit housing models that maintain affordability for the life of the building and limit profits for owners, as is the case in Austria.

What makes you hopeful about housing in Vienna?

Social housing isn’t stigmatized or controversial, and powerful laws ensuring affordability are backed by the historical success of housing co-ops. The Limited-Profit Housing Act requires that social housing remain affordable indefinitely and that rents remain low. The limited-profit organizations that manage today’s social housing are required by the Limited-Profit Housing Act to meet strict financial responsibility metrics. Austrian policies incentivize responsible management of affordable housing and all profits must be reinvested. In exchange, owners are incentivized by corporate income tax exemptions and access to government subsidies. Many Austrians are proud of their stable and well-regulated affordable housing industry, which serves a large percentage of the population.

What are effective ways to include the people most impacted by affordable housing issues in government-level decision making?

There are a number of NGOs that act both as social services agencies for people in need and as lobby institutions for those populations. These NGOs work with Austria’s limited-profit housing associations to execute rental contracts that allow NGOs to sublet units to refugees or other groups. They also develop affordable housing for particular populations in partnership with limited-profit housing associations. NGOs use this housing experience and exposure to to create programs and lobby for policies that benefit those with the greatest needs.